An all to common Occurrence

One of the fundamental reasons, amongst the many, we lost the battle of hearts and minds is that we were unwilling, at least in the beginning, to expose our selves to the necessary risk to properly engage the Iraqi population. Our rules of engagement, although meant to give Iraqis every reasonable opportunity to show they are not a threat, did lead to many civilian deaths in Iraq. We treated everyone as if they were a threat. Combine with a lack of cultural knowledge, and we set up to lose from the onset.

Consider these all two common scenarios:

You are driving down the road to market. You approach a U.S. convoy moving slowly as they always seem to; however, you are not paying too much attention to the road, and moments later you are within the 100 meters of the U.S. convoy. The U.S. solider, alert and surprised the car has failed to take heed of his warning to stop, opens fire on the car killing the driver. An investigation would be opened to ensure the soldier acted in accordance with the rules of engagement, and the simple truth is, the soldier did act within the rules of engagement.

This next scenario has to with common day-to-day life hassles. When approaching U.S. forces on foot, an Iraqi can expect to have a weapon pointed at them and to be searched. Imagine walking to a friend’s house, and being stopped by the police at gunpoint and searched for no reason. These types of interactions do not foster feelings of happiness or trust.

These two incidents did not occur out of malice on behalf of U.S. soldiers, but rather as a result of policy makers aversion to risk. We often failed to mitigate risk in a manner that would not place such strain on U.S.-Iraqi relations. The fact we treated every Iraqi as a threat lead to a culture of mistrust between the two.

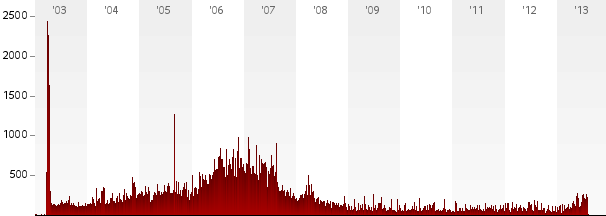

Sadly, many of our policies have resulted in many Iraqi civilian deaths. These deaths left a sour taste lingering. Iraqbodycount.org has extensive information on how Iraqi deaths directly related to U.S. combat actions. Their data has been used in congressional hearings and other governmental agencies alike.

Chart Showing Iraqi Civilian Casualties

Source: http://www.iraqbodycount.org/database/This distance also put much distance between U.S. and Iraqi to better understand the other’s culture.

The American ignorance of Iraqi culture is similar to the cultural misconceptions Tomlinson describes that occur when viewing culture from the protective bubble composed of the intrinsic unevenness globalism. Americans soldiers live a life of relative luxury while deployed to Iraq. I must stress this “luxury” is “relative” in the strongest sense of the word. Take for example simple luxuries that became necessities in developed countries: showers, hot water, air conditioning and the like. All of theses items are wonderful to have, but are not required for the sustainment of life, and in a lesser developed country, these are the luxuries of the elite. Additionally, the average soldier spends his tour in Iraq behind a literal and metaphoric walls of protections. These protections put a distance between the soldier and the Iraqi culture. This distance often resulted in soldiers not attaining a good understanding of how the culture works and ill-faited attempts to win over the population or realistic expectations.

For example, When I first arrived at Al-Rasheed (the military based I shared with 9th IA, BDC) temperatures and expectations were high. A week would pass before the flood gate of emails burst open with the intensity of an exploding bomb.Where are my results the emails proclaimed. There was a misconception that the IA was lazy or unwilling to cooperate, that they were stonewalling. What the Command failed to understand, was Iraqi culture values personal relationships and family over business, and a rapport must be established before business may be discussed. And that is what we were doing at the guidance of teams that came before us. Teams that lived the culture and ate the food. This was my first true lesson and experience in global affairs/globalism: Differences in culture are there (there is no one homogenized global culture) and you must be willing to work with the local culture. As that statement implies, you have to travel beyond the protections seeking to minimalize the intrusions of foreign cultures to genuinely understand the culture of the locale. As Tomlinson, points out, this protection for the business class are air ports, common standardized hotels, and the like; for the soldier of a developed country it is the walls, guns, and other protections designed to put distance between American soldiers and the Iraqi people for the sake of safety and comfort.

So we combine an aversion to risk that leads us to adopt policies that put the Iraqi in our harms way, and then not understand their culture, we will only create frustration.

We should have worked harder to establish Iraqi Governance more quickly, and we should have worked more closely with the local population, not behind the sights of guns, but with sound cultural understanding. Doing so, in hindsight, may have helped win the Iraqi hearts and minds.

Speak your mind